Despite the gloom and doom of the new year, there is reason to feel good about the U.S. job market.

The news from the dark side is that oil prices are down, the equity markets are volatile, it is an election year, and there is uncertainty about the global economy….There are always headwinds.

On the sunny side of the street, there is plenty of upside:

• Unemployment is 4.9%.

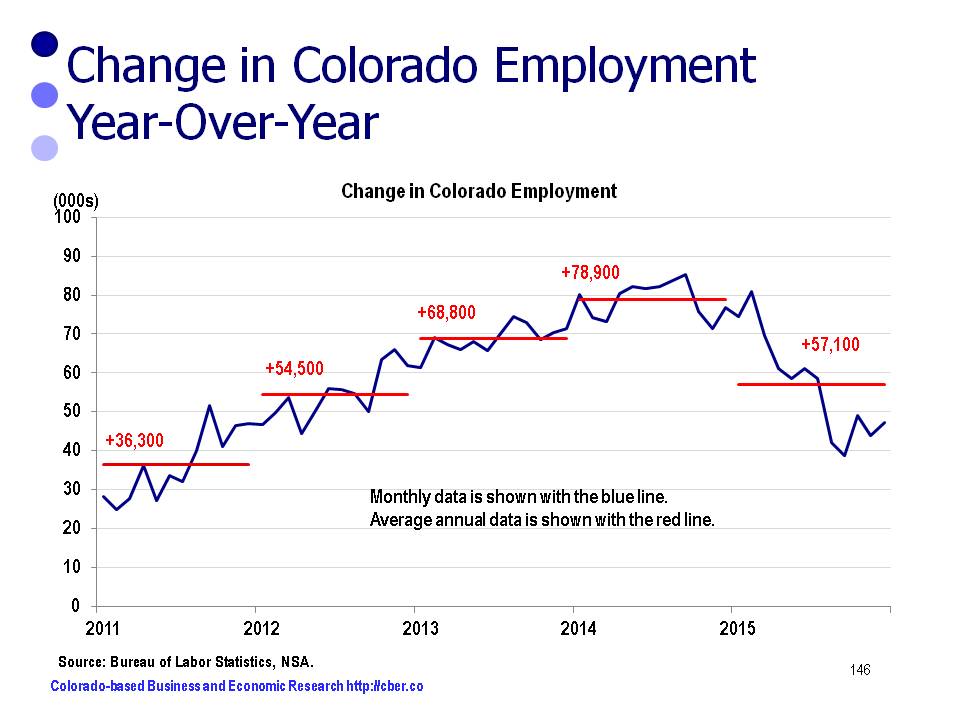

• About 10 million jobs were added in the last four years (2012 to 2015).

• Weekly initial jobless claims have been below 300,000 for about a year.

• The recent growth in wages exceeds the rate of inflation.

• Low gasoline prices have fueled greater saving and consumption.

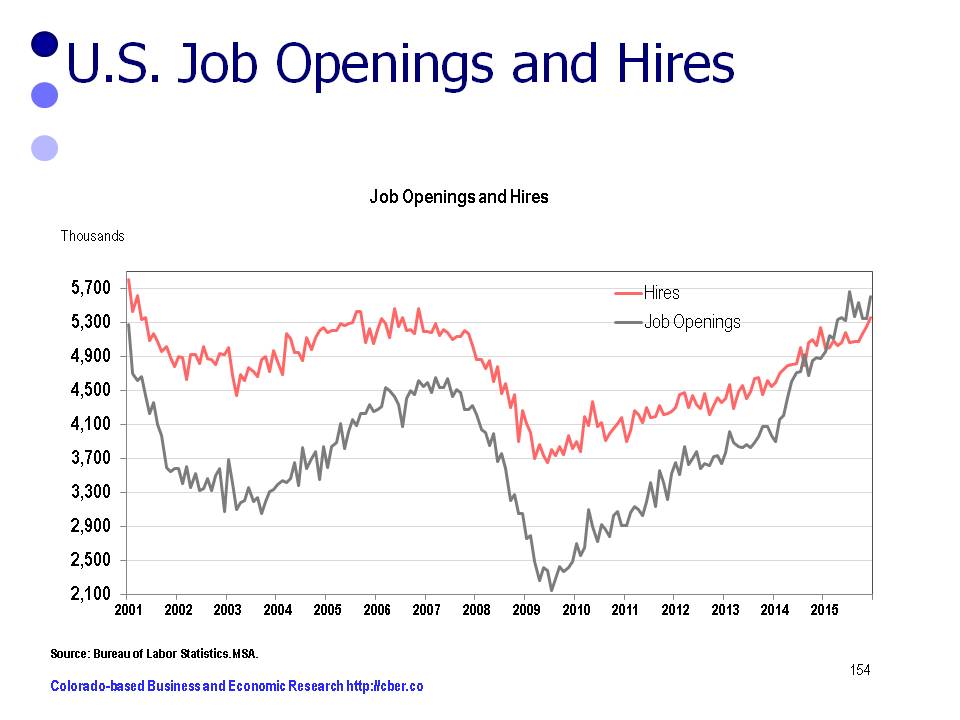

Another data series that points to a solid U.S. job market is the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). This infrequency cited database tracks job openings, hires, and separations. They are defined by the BLS as follows:

• Job Openings – All positions that are not filled on the last business day of the month.

• Hires – All additions to the payroll during the month.

• Separations – all employees separated from the payroll during the months.

During periods of economic growth, the number of openings (grey) and hires (red) increases. When the growth of the economy slows as it did in 2001 and 2008 there is a decline in the number of openings and hires. At present both openings and hires are trending upwards.

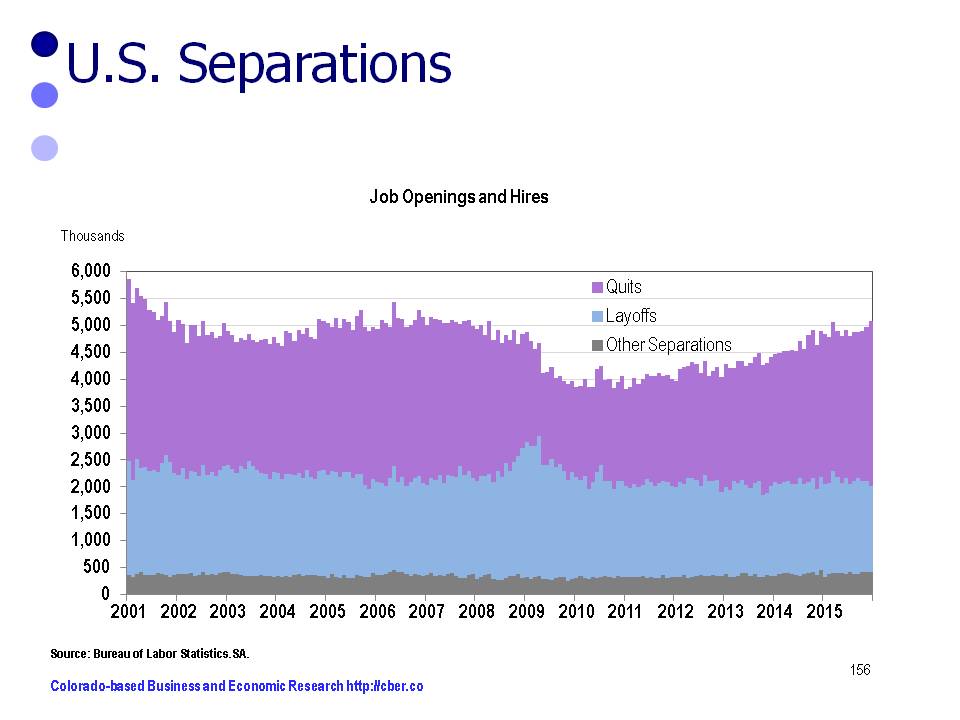

A closer look at separations shows there are positive trends in its three series (other, quits, layoffs). These series are defined as follows:

• Other Separations – retirements; transfers to other locations; deaths; or separations due to employee disability.

• Quits – Employees who leave a company voluntarily.

• Layoffs and Discharges – Involuntary separations initiated by the employer.

Currently, other separations (grey) are flat, layoffs (blue) and discharges are flat or trending downward, and quits (purple) are increasing. These are indicators of a healthy economy.

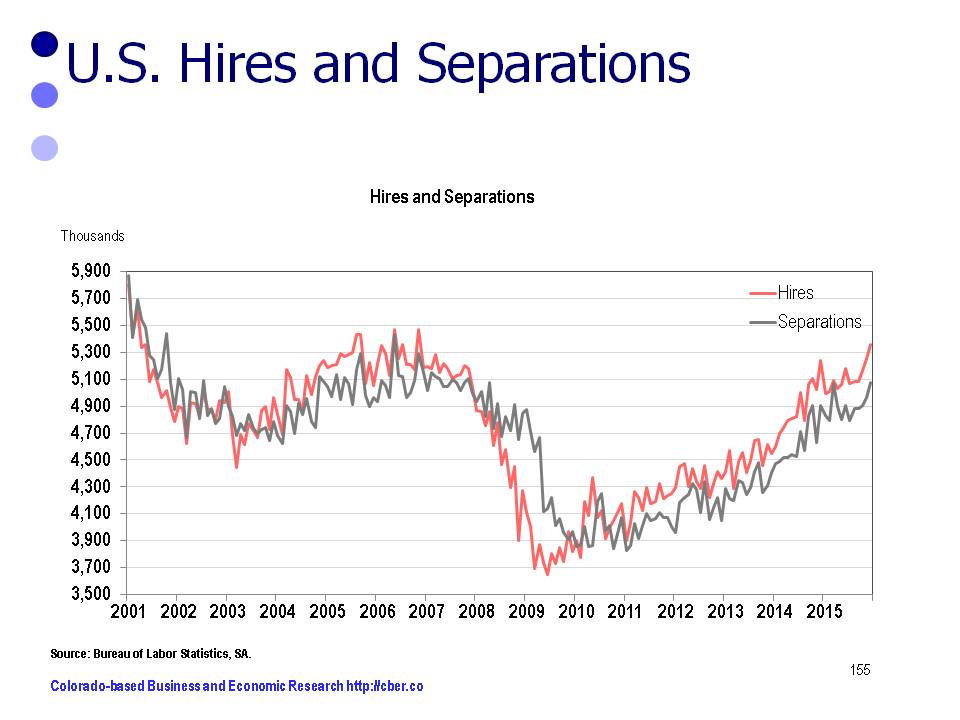

As mentioned earlier, the number of hires moves in conjunction with the performance of the economy. During 2008 and 2009 the number of hires declined sharply. At the same time, the number of separations (grey) declined at a much slower rate, i.e. the number of layoffs increased significantly. The result is the massive job losses associated with the Great Recession.

Since 2010, both hires and separations have trended upwards. As there are more job hires, more people quit their jobs to take positions with other companies.

The bottom line – the U.S. job market appears to be on solid footing for the moment.